UCLan academic in team that discovers regular rhythms among pulsating stars

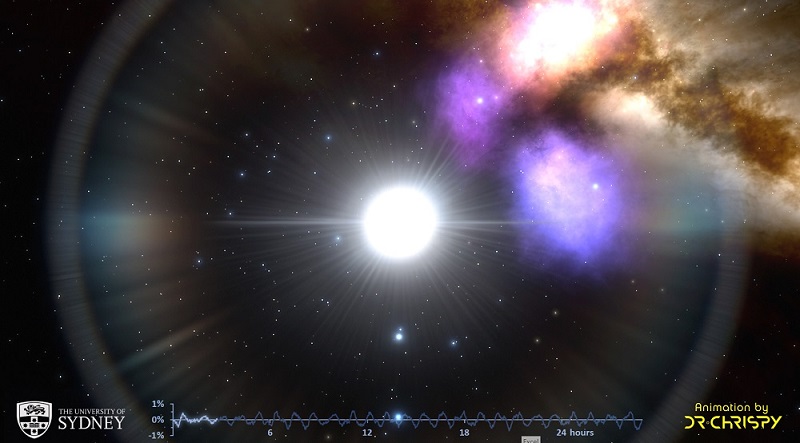

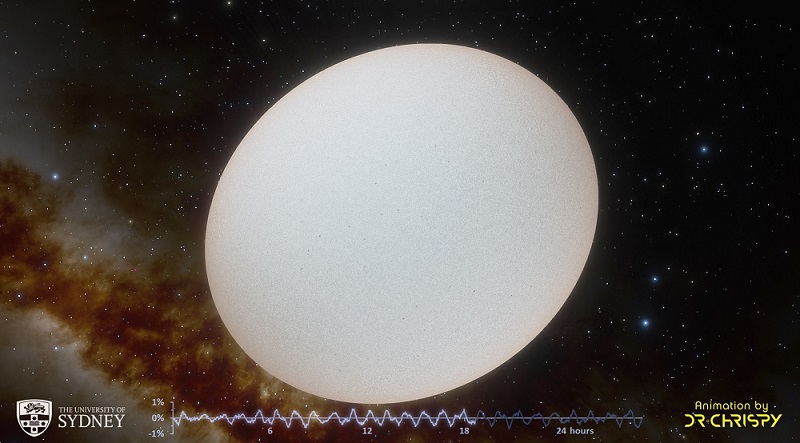

By listening to the beating hearts of stars, international astronomers have for the first time identified a rhythm of life for a class of stellar objects that had until now puzzled scientists.

Dr Daniel Holdsworth, from the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), is part of the global team whose new findings have been published today, 13 May, in the prestigious Nature journal.

Lead author Professor Tim Bedding, from the University of Sydney, said: “Previously we were finding too many jumbled up notes to understand these pulsating stars properly. It was a mess, like listening to a cat walking on a piano.”

The international team used data from NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), a space telescope mainly used to detect planets around some of the nearest stars to Earth. It provided the team with brightness measurements of thousands of stars, allowing them to find 60 whose pulsations made sense.

“The incredibly precise data from NASA’s TESS mission have allowed us to cut through the noise. Now we can detect structure, more like listening to nice chords being played on the piano,” Professor Bedding said.

The findings are an important contribution to our overall understanding of the processes that occur inside the billions of stars in the Milky Way.

The intermediate-sized stars in question – about 1.5 to 2.5 times the mass of our Sun – are known as delta Scuti stars, named after a variable star in the constellation Scutum. When studying the pulsations of this class of stars, astronomers had previously detected many pulsations, but had been unable to determine any clear patterns.

The Australian-led team of astronomers has reported the detection of remarkably regular high-frequency pulsation modes in 60 delta Scuti stars, ranging from 60 to 1,400 light years away.

“This definitive identification of pulsation modes opens up a new way by which we can determine the masses, ages and internal structures of these stars,” Professor Bedding said.

Dr Holdsworth, Research Associate in Asteroseismology at UCLan, was one of four UK based academics to work on the research. His research was funded by the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).

He commented: “These findings have opened a new window on the analysis, and so understanding, of the delta Scuti stars. Previously it has been hard to identify patterns in the pulsation modes in these stars, and it is the regular patters which hold the key to understanding the physics at play in the stellar interiors. Although the 60 stars studied in the paper represent just a small fraction of the total delta Scuti population, these results will have implications for future studies.

“For example, we have shown that these stars are young, they are just starting the main part of their life, so we can use the information about regular spacings in other delta Scuti stars as an age diagnostic. The age of a star, or groups of stars, can be hard to determine with results differing by a factor of two. However, asteroseismology has the power to provide very precise ages thus providing the opportunity to expand our understanding of the Galaxy around us.”

Daniel Hey, a PhD student at the University of Sydney and co-author on the paper, designed the software that allowed the team to process the TESS data.

He said: “We needed to process all 92,000 light curves, which measure a star’s brightness over time. From here we had to cut through the noise, leaving us with the clear patterns of the 60 stars identified in the study. Using the open-source Python library, Lightkurve, we managed to process all of the light curve data on my university desktop computer in a just few days.”

The insides of stars were once a mystery to science. But in the past few decades, astronomers have been able to detect the internal oscillations of stars, revealing their structure. They do this by studying stellar pulsations using precise measurements of changes in light output.

Over periods of time, variations in the data reveal intricate – and often regular – patterns, allowing us to stare into the very heart of the massive nuclear furnaces that power the universe.

This branch of science, known as asteroseismology, allows us to not only understand the workings of distant stars, but to fathom how our own Sun produces sunspots, flares and deep structural movement. Applied to the Sun, it gives highly accurate information about its temperature, chemical make-up and even production of neutrinos, which could prove important in our hunt for dark matter.

Professor Bedding added: “Asteroseismology is a powerful tool by which we can understand a broad range of stars. This has been done with great success for many classes of pulsators including low-mass Sun-like stars, red giants, high-mass stars and white dwarfs. The delta Scuti stars had perplexed us until now.”

Isabel Colman, a co-author and PhD student at the University of Sydney, said: “I think it’s incredible that we can use techniques like this to look at the insides of stars.

“Some of the stars in our sample host planets, including beta Pictoris, just 60 light years from Earth. The more we know about stars, the more we learn about their potential effects on their planets.”

The identification of regular patterns in these intermediate-mass stars will expand the reach of asteroseismology to new frontiers, Professor Bedding said. For example, it will allow us to determine the ages of young moving groups, clusters and stellar streams.

“Our results show that this class of stars is very young and some tend to hang around in loose associations. They haven’t got the idea of ‘social distancing’ rules yet,” Professor Bedding said.

Dr George Ricker, from the MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research is Principal Investigator for NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Sky Survey, added: “We are thrilled that TESS data is being used by astronomers throughout the world to deepen our knowledge of stellar processes. The findings in this exciting new paper led by Tim Bedding have opened up entirely new horizons for better understanding a whole class of stars.”

An animation, complete with sound, can be viewed on YouTube, and the research paper can be viewed online.