Alternative Blue Plaque Reclaims the Lancashire Mill Poetess on International Women’s Day

An alternative Blue Plaque will travel key places in the life of a forgotten working-class heroine on International Women’s Day on 8 March, 2022.

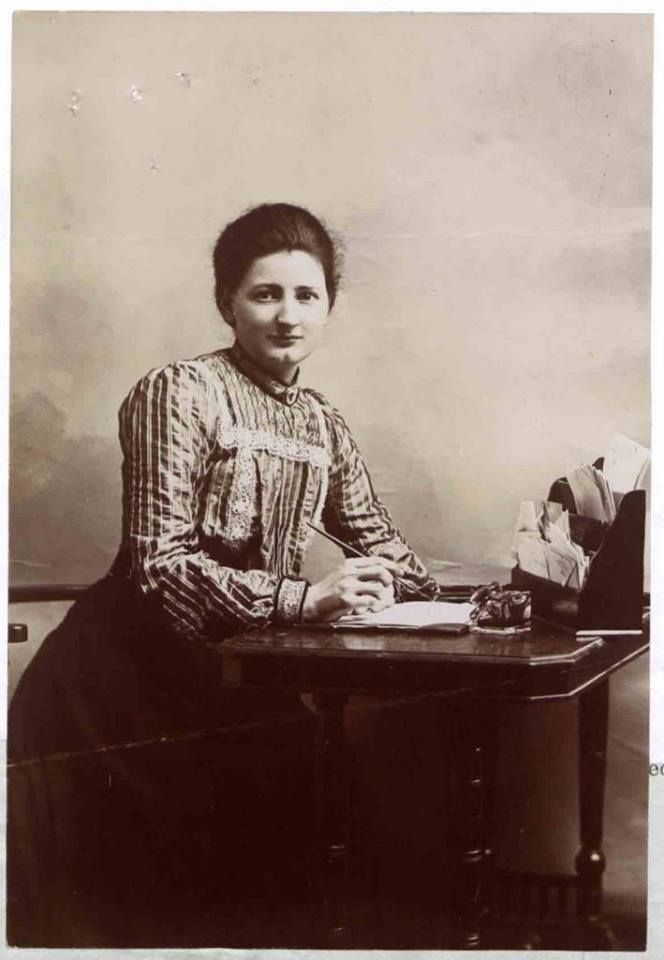

Activist, poet, journalist and author Ethel Carnie Holdsworth (Born Oswaldtwistle 1886- Died 1962), is believed to be the first working-class woman in Britain to publish a novel.

Pendle Radicals, a research and creative project led by Mid Pennine Arts, explores stories of Pendle Hill’s radical thinkers. They contacted the art collective Rosie’s Plaques to help identify uncelebrated female radicals, deserving of a plaque.

Janet Swan, Project Lead at Pendle Radicals on Ethel’s story, said: “The alternative plaque will be installed at Ethel’s old home for International Women’s Day. She was remarkable as a writer, a woman and an activist. It’s time her name is celebrated and known more widely.”

Rosie’s Plaques began the alternative plaques after finding out that of the 4,500 heritage blue plaques in the UK, less than 12% celebrate women.

Eighteen volunteers from Pendle Radicals and Rosie’s Plaques will take the plaque on a journey to mark key moments and events in Ethel’s life.

They will set off from Glebe Street Great Harwood at 10.30am in a vintage bus. Great Harwood is where Ethel went to school, and is the site of the mill where Ethel worked as a half timer.

The bus will then go on to locations where Ethel grew up and had formative experiences, including the Co-operative Reading Rooms, where she acquired the love of reading.

The journey will end at the house at Slack Top, Heptonstall, where Ethel lived while producing The Clear Light – the anti-fascist newspaper that even in the 1920s warned of the threat of Mussolini.

Here, the Hebden Bridge filmmaker, Nick Wilding, will talk about a recently unearthed 1920s silent film – an adaptation of one of Ethel’s books, Helen of Four Gates. The book was a bestseller in the UK and in the US, at the time outselling HG Wells two-fold. The silent film had been lost for 80 years until it was recently discovered at auction.

The alternative blue plaque marking Ethel’s life will be gifted to the current owners of the house.

At each pitstop, volunteers will read Ethel’s poems, which were inspired by the rhythm of the looms and key passages from her books and articles. They will also sing the songs that Ethel and her mill worker colleagues would have sung that depict Ethel’s beliefs in workers’ rights, equity, and fairness for women.

Janet Swan said: “Mill workers used to read secretly to steel themselves against the gruelling work of the mills. Reading opens doorways to new worlds and ideas and transports imaginations. Ethel’s books offered not just escapism but inspired working women worldwide.”

Pendle Radicals is supported by the Pendle Hill Landscape Partnership, a National Lottery Heritage Funded project.

The team is liaising with academic Jenny Harper, who is undertaking a PhD to explore Ethel’s literary significance and track down her lost works.

Other academics helping reclaim Ethel include Dr Nicola Wilson, who championed the republication of Ethel’s fiction. A single remaining copy found on e-Bay of Ethel’s long-lost novel The House That Jill Built is being used to re-print the novel, due out later this year.

The House That Jill Built considers the topic of women finding safety and refuge from the exhausting double burden of paid work in addition to all family and domestic work; a very modern topic in 1924. Ethel used the boom time in women buying and reading romantic fiction to bring socialist ideas to women, to help them to change their own lives.

The first edition of the book will be added to a few other similar items collected by enthusiastic academics and by Ethel’s niece, who owns first edition poetry and fiction books, complete with inscriptions, and never before seen letters and photos.

Pendle Radicals have also created a new podcast series about Ethel; as well as placing some of her poems in the Poetry Archive.

Writer, campaigner and activist Ethel (born in Oswaldtwistle) began working in the mills aged 11. She became known as the ‘Lancashire mill girl poetess’ by the local paper, after she claimed that the rhythm of the looms helped her write her poetry.

Ethel also helped other working-class women learn to read and write, and tell their own stories at a time when women’s voices weren’t being heard.

She was anti-war and anti-conscription in the build up to the First World War, and one of the first to realise the threat of Mussolini.

At one anti-conscription meeting called by the British Citizen Party, and presided over by Ethel, she took refuge on top of a grand piano after a huge brawl broke out as the local Home Defence Corps tried to break up the meeting.

A local newspaper report described it as “one of the rowdiest gatherings in the history of Nelson.”

The reporter wrote: “Blows continued to be exchanged. Although the (male) speakers left the platform, the chairwoman stuck to her post, but later found it advisable to seek refuge on the top of a grand piano.”

Her politics, alongside the impact and mould-breaking significance of her writing, puts her on a par with the male writer, Robert Tressell, yet she hasn’t been as championed.

Janet Swan added that Ethel would be a much-needed and inspirational figure today: “She speaks to individuals, inspiring us to cherish our collective power and heritage. She would have us all doing something to work together instead of living with this huge gap in society exacerbated by the pandemic; those who use food banks versus those who have profited.”